About 15 years ago, my dad built a 1/6th scale radio controlled flying model of Charles Lindbergh’s iconic Ryan NYP, better known as The Spirit of St. Louis. In the two years he spent constructing his 91″ replica, dad extensively researched Lindbergh’s life and seminal, 1927 New York-to-Paris flight. This research showed in the meticulous detail of his plane. Every detail is represented in immaculate miniature — from Lindbergh’s uncomfortable wicker seat, to each and every one of his instrument panel gauges, to a tiny working version of his side periscope complete with mirrors. Dad’s research gave him enough expertise that he could see un-captioned photos of the plane and know when and usually where they were taken. He even uncovered inaccuracies in some of the written accounts. However, one detail escaped him: the golden nose.

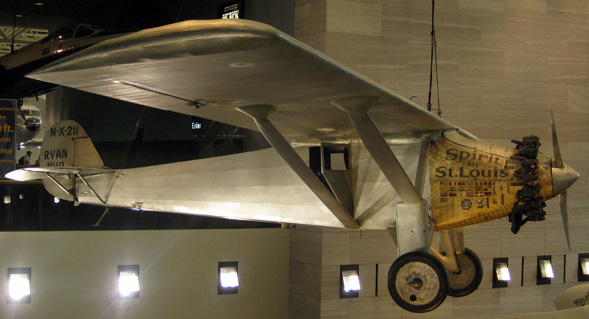

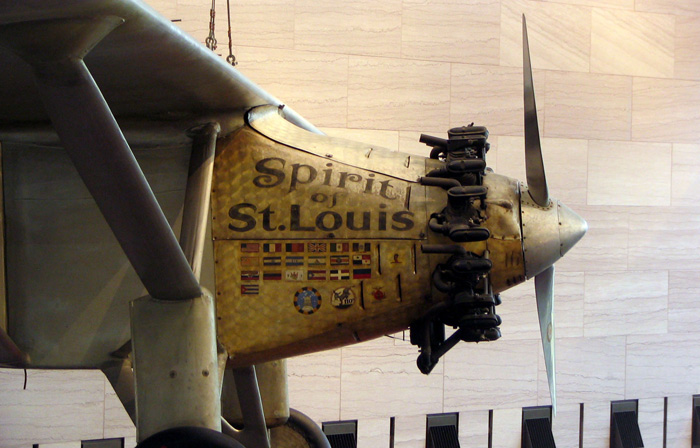

When it crossed the Atlantic, the Spirit of St. Louis had a silver nose. The whole plane was silver from tip to tail. The nose panels in particular were fabricated by hand out of aluminum sheeting. Those panels were then brush polished with their signature swirl marks — partly for decoration, but mostly to hide the subtle dents left by shaping hammers and english wheels. In the period photography, even though it’s black and white, it’s easy to see that the nose is not, in fact, gold. Yet as she hangs in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, her nose is a bright gold color. None of the historical accounts, including Lindbergh’s autobiography, explained how the nose of the plane went from silver to gold. It was a mystery, and 15 years ago the internet as we know it didn’t exist. We often said that we should just write the Smithsonian and see if they knew, but we never got around to it.

Today people use Google as a verb and Wikipedia makes the most obscure pieces of information available to your mobile telephone. For some unknowable reason, yesterday I had the thought to search the internet for information as to why the nose on The Spirit is gold. The search engines had nothing for me. Wikipedia made no reference to the nose panels whatsoever. Even the Air and Space Museum’s own website didn’t explain the golden nose. But while poking around, I found a contact form where anyone can send an inquiry to the museum archives staff. So I did! I got an email back a couple hours later saying that my question had been forwarded on to the curator. Less than a day later, I received an email from Dr. F. Robert van der Linden, the Chairman of the Aeronautics Division at the National Air and Space Museum. In his email he said the following:

Dear Mr. Salzman:

The nose of the Spirit of St. Louis is a golden color because of a well-intentioned but mistaken attempt by us to preserve the markings on the cowling. We don’t know exactly when, but soon after the Smithsonian acquired the Spirit in May 1928, we sought to preserve the markings by applying a clear coat of varnish or shellac. Unfortunately, over the years, this coating has yellowed with age. While it has taken on a beautiful golden hue, the color is wrong. The aluminum cowling should be in its natural silver color. In the future, when we next conserve the aircraft, we will carefully remove the coating. This can be done by a painting conservator. Until then, the Spirit will keep its golden nose.

Sincerely,

Bob

What a fantastic answer! Although it would be great to know exactly when the protective lacquer had been applied, finally knowing the the answer as to why is very satisfying. As far as I know, this information isn’t even part of the exhibit. Not that it’s a big secret, it’s just fun to know things that even the great Google can’t find for you. What’s particularly thrilling, however, is that at some point in the future, the plane will go back to its original coloring. How fun. I’m exceedingly grateful to Dr. van der Linden for his quick, complete and candid response. Mystery solved. With information in hand, it’s now time to update the internet so that other people can find this info too. The moral of the story, support the historical societies that protect the history you care about. Without them, we will forget where we’ve come from and have even less idea where we’re headed.

Photos via Flickr users Rob Shenk and wallyg who were kind enough to share their great work via creative commons licensing.

I’ve wanted to know that for years!! Thank you so much!!

I also wondered why the replicas were all silver but the actual plane being preserved had the “golden nose”. I found a site that said that it turned gold because of some sort of chromatic paint that was used back then. I continued my research unsatisfied and came across your blog. Thank you for taking the time to reach out and get that information; It’s nice to finally know the answer as I feel better about getting the all-silver replica. :P

Well, as Wil Wheaton is fond of saying, “I love living in the future.” All I did was surf the Smithsonian’s website and find the contact info for the Air & Space Museum. Thankfully, the curator was kind enough to reply to my email. It’s an unexpected explanation, but as he told me, the nose will be silver again soon enough.

Thanks Nathaniel, Thanks. I was repairing models I built back in the 60s and the SoSTL was one of them, and I wanted to know about the cowl. If I had a vote in what was to happen to the nose, mine would be to leave it gold with a note explaining. The man, the people, the flight, the importance and the instant recognition of its history and donation to display the plane forever are ALL history — golden hue included. Robert Atkinson