“Are you ready for a real bike?”

Robb projected his question over the growl of The Mrs’ Honda CM400 as I pulled up to the open door at BlueCat Motors. Out front was my green Honda CB750. That was the bike in question. It’d been a few days since I’d seen the old boy. When last we’d met, I’d just finished cleaning and installing the carbs, rebuilt the front brakes and installed a brand new battery. But for all my efforts, the thing still didn’t run. I’d hit my limit, but thankfully, I wasn’t on my own. I was in good hands at BCM. My bike had been handed off to Robb and with it, my hopes to actually get some riding in this season.

Autumn in Minnesota is unpredictable. You might be able to ride into Christmas, or it might blizzard on Halloween. So I was glad to leave the CB750 in the hands of a professional. I knew I’d actually get to ride it before things got too cold and uncomfortable.

Robb had accomplished in a couple days what would have likely taken me weeks. More than that, he’d been over the bike from wheel to wheel. He’d flushed and bled the brakes. He’d inspected and adjusted my charging system. He’d re-aimed my headlight. The carbs were synced and Robb had taken the bike out himself to make sure it was running and riding like it should. “Both Rumpal and I rode it and the thing really comes alive at 4000 rpms. You’re going to have a blast.” Beyond the running, Robb had adjusted the suspension as well. “It’s got the most air it will take up front and it’s on full stiff on the rear shocks. It’s a bit harsh for both me and Rump, so it ought to be perfect for you.” He was right on both counts.

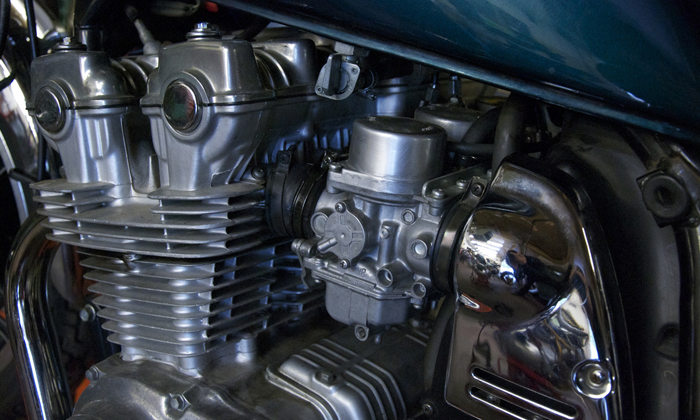

I stowed the CM400 inside (I’d be trading it back for the GL in a few days) and met Robb at the CB750. A little bit of choke, key on, and with a deliberate press of the starter button the 750 fired to life. It hummed happily and revved easily. For all their faults, there’s something special about an inline four cylinder that’s freshly synced. They’re so smooth, so howlingly eager. Robb made a couple final adjustments to the idle speed as the bike hummed and growled through its four chrome exhaust pipes. When he was satisfied, Robb gave me one final instruction. “I want you to ride the hell out of this thing. Seriously. Work it hard for a while and burn all the crud out of the cylinders. It’s been sitting for so long, some good, angry riding is exactly what it needs.”

Yes sir.

I threw a leg over the 750 and felt the machine growling under me for the first time. It seemed anxious — an iron horse spitting and whinnying — aching to gallop and shake off half a decade’s worth of boredom. I walked the bike forward off its center stand and we were ready to go. It’s a tall, top-heavy thing, just like every CB750. Clutch in, I tamped down into first gear. Giving it some throttle, I searched for the clutch engagement point to set off. Thanks to a down-geared front sprocket, this 750 took off eagerly and easily, unlike its stock siblings. I reached the end of the BCM lot and pulled onto Prior Avenue, headed toward I-94 and opening the taps for the first time on this proto-superbike, unleashing its 77 hp onto the streets of St. Paul. Within a moment, I was at the I-94 onramp and it was time to see what the 750 was capable of in its second lease on life.

Robb was absolutely right. Above 4000 rpm, the CB750 started pulling really, really hard. The down-geared sprocket meant keeping the bike in the sweet spot of its power band was effortless. What’s more, fifth gear was suitable for speeds of 50 mph and up — making this a one gear bike on the freeway. Open up the carbs and fresh gas is turned into lots of noise and speed, no downshifting required. It was a Friday afternoon, just after rush hour, so there was plenty of traffic on I-94, but it was all moving well. Robb had gotten the suspension adjustment just right for someone my size. The bike was stiff, but not uncomfortable. It was sporting, and perfectly balanced front to back. The 750 begged for aggressive riding. I obliged.

I’m not any kind of hooligan rider, and really, the CB750 isn’t a hooligan bike. More than anything, the aggressive, effective brakes together with the power and the adjustable suspension made this old CB750 a sport bike disguised as an old cruiser. The teardrop tank on this pre-Nighthawk Honda looks like it could have come off a Triumph. But give it the beans and the CB750 will outrun damn near anything trying to catch it. More importantly, it’s got the suspension and brakes under it to help keep you out of trouble at such speeds. As I shot down I-94, I was threading through traffic with no effort at all. The howl of four cylinders and four pipes made the CB750 sound more like an old Italian sports car than a modern motorcycle. It lacked the childish scream of many sport bikes. Most of all, I liked how unexpected it is. It’s a good looking motorcycle, but it’s not a bike the untrained eye would give a second look. It’s a sleeper. It doesn’t look fast, but it is. Not fast by contemporary superbike standards, but fast enough for me. Fast enough to be scary. Fast enough to be really, really fun.

More than anything though, the CB750 was forgiving. It was tight enough to be precise, but civilized enough to simply be ridden. There was no tending it — no having to stay ahead of it to make sure it didn’t reach up and bite me. I didn’t have to dodge every little bump and frost cleave on the highway. It was a bike I could simply sit on and enjoy. It was grown up. It was fast. It was confident. It was fun. Best of all, it was mine. I finally had a bike of my own. After a full season of false starts, mechanical difficulties, and stealing my wife’s motorcycle for a ride, there would finally be a bike for me in the garage. The Mrs and I could finally ride motorcycles together, something we hadn’t gotten to do all season. My rebuilding year would at least end with an autumn of good riding.

After a handful of spirited runs up and down I-94, I circled back to BlueCat Motors with a big grin on my face. I gave Robb a report on the bike’s performance and thanked him not just for his quick work, but for all his attention to detail. He’d found and sorted things with the bike I didn’t even know were wrong with it. While writing for the BCM blog, I’ve seen how Robb works on bikes. Any machine that makes its way onto his lift won’t leave the shop until it’s right — even if that means fixing something the customer didn’t bring the bike in for. He takes his responsibility as a mechanic very, very seriously. If I wasn’t going to sort this bike out myself, I’m glad it was Robb. Not only did I end up with a bike that runs, I ended up with a motorcycle I knew I could trust. That’s what made it a real bike.

I rode home, taking more of the highway than I usually do on The Mrs’ smaller CM400. There’s one particular part of I-35E South that I wanted to push the CB750 through. It’s the interchange where 35E meets 494. North of the interchange, the speed limit is 55 mph or 60 mph depending on what road you’re on. The southbound leg of 35E takes a sweeping right turn and immediately changes up to a 70 mph speed limit and widens to four lanes. What I love to do here is slingshot around the corner and put on some speed. I’d taken Robb’s advice about the 750 to heart and this was the perfect place to put it into practice. “Ride it hard,” he’d said. When that big sweeping turn came up, I opened the throttle all the way.

A quick lane change had me blasting around the sunset traffic. It’s two exits to Yankee Doodle, where I usually turn off to go home, but I kept hurtling down the highway. I left the taps open and poured on as much speed as I dared. The tires on this old machine had sat as long as the rest of the bike. While not cracked or obviously weather checked, I still didn’t trust them fully. So while I didn’t bury the speedometer completely, I made the old boy work for his hay and oats. The harder I pushed it, the smoother and sweeter the engine seemed to get. The old bike was now fully back to life, and it seemed like the old machine’s soul was grateful for another chance. The old horse was thrilled to gallop once again.

![]()

I’m jealous!

Great to hear it’s running again! …and getting some quality attention.

Thanks for the update.

Ahh yes! I love my 81 Yamaha 650. Not pretty, but just like you said, it’s got it where it counts! This post got me jonesin’ for a ride a BCM tune-up!!! Thanks!